1916-1923

Every art movement listed on this website is presented with its unique characteristics so if you happen to walk into a museum, you could easily identify to which movement an artwork belongs. In the domain of Dada art, that might not be possible for two reasons. One, well, there is no movement, at least not an official one. Hence there is no common characteristics among the artworks, heck, they don’t even call their productions art! They used everyday objects to make an anti-art statement. Then to make matters more confusing, their approach using mundane objects became an art movement in its own right in the second half of twentieth century called Conceptual Art. However, there are some elements that bring together the work of Dada artists which are distinct from that of Conceptual artists who would emerge decades later.

1. Iconoclastic and playful.

Art had long thrived on rebelliousness, but the Dada artists were not just disrespectful, they physically attacked traditional art and defaced it. Dark and irreverent humor was always a theme in their works.

Marcel Duchamp, La Joconde/ L.H.O.O.Q., 1919

Marcel Duchamp painted a mustache and a goatee on a reproduction post card of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. He wrote at the bottom the letters “L.H.O.O.Q.” which is a pun in French. When pronounced, it sounds like “Elle a chaud au cul,” meaning “she has a hot arse” or “she’s horny.”

Francis Picabia’s Nature Morte: Portrait of Cézanne/Portrait of Renoir/Portrait of Rembrandt (1920)

The French painter nailed a toy monkey to a board and around it he wrote names of three of the greatest artists.

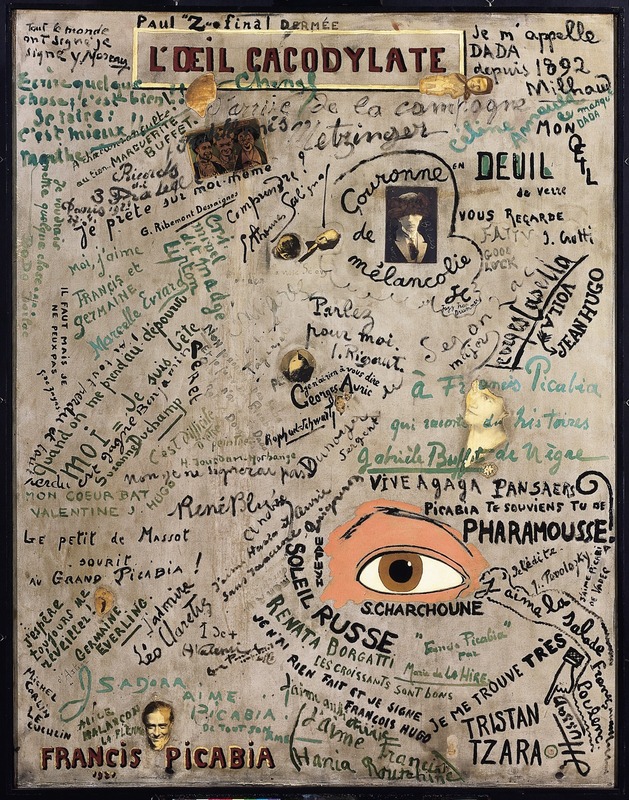

Francis Picabia. L’Œil cacodylate (The Cacodylic Eye). 1921

Legend has it that the artist contributed only his signature and date. He created this while hospitalized for an infection in his eye. He invited all his friends as they visited him to contribute something. It was a radical collaborative work, the earliest of its kind.

2. Illogical and absurd

Dada artists relied on madness and absurdity to shock their audience. You could find that in a blurred photo with creepy double eyes or a laundry iron with spikes! The iron in particular stands for another common theme in their art, that is the use of everyday objects (next characteristic on the list below).

Man Ray, Marquise Casati (1922)

3. “Readymades”: everyday objects as art

What Dadaists were notorious for was their challenge of the accepted definition of art. They pioneered what became a post-modern feature later in the twentieth-century. Today we call that conceptual or installation art. Theirs was different in the way that they put on display what they considered absurd: a coat rack or a urinal! Then they couldn’t believe it when they were taken seriously. The mass-produced objects, they called “Readymades,” which they would buy from local stores had no aesthetic value, yet when submitted to art exhibits, they were accepted! They philosophized it by declaring, as bizarre as it sounds, that artists no longer need to be the creators of their own art. The most outrageous act in that vein was Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain.” He bought a porcelain urinal, gave it the humorous title, turned it upside down and signed it “R. Mutt” in reference to the manufacturer and a character in a comic strip. Today we consider it one of the most important works of the last century because it forced us to question our understanding of art. Decades later, Andy Warhol would famously employ similar ordinary objects for art. On another occasion, he mounted a wheel on a kitchen stool and called it “Bicycle Wheel.”

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (an upside down urinal), 1917

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1951 (the 1913 original was lost)

Hat Rack (1917) by Marcel Duchamp

The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse (1920) by Man Ray

4. Collages and disturbing photomontages

The artistic collage, made up of different materials and fragments of printed text, was a Cubist invention, preceding Dada art by several years, however the Dadaists endorsed it to some extent. The Dada collages you will encounter are not many, and those you find will not be easily distinguishable from the Cubist type. If Cubist artists tried to convince us that a collage of various materials can be refined art, the Dada artists tried to do the opposite, i.e. they were turning that medium into anti-art. They did not even call them collages, that sounded “too artistic.” Instead, they pioneered the now-familiar “photomontages” because it evoked machine production and no personal artistic involvement. (Note: While collages bring together different materials, a photomontage is mainly cut-out photographs.)

Although most of their collages were photomontages, there were a few non-photographic ones like Arp’s iconic work to which he did not give a title. He created the collage by arbitrarily dropping torn rectangular pieces of paper on the canvas, or at least that was his story!

Jean (Hans) Arp. Untitled (Collage with Squares Arranged according to the Law of Chance). 1916–17.

Kurt Schwitters, Merz 19, 1920. Paper collage.

While Cubist collages tried to display harmony and beauty, Data photomontages were brutal and disturbing. The Dada artists emerging from the shadow of the WWI horrors, focused mainly on violent imagery and nonsensical juxtapositions.

Hannah Höch’s work (view below) is an iconic example of a chaotic Dada photomontage. Its ridiculously long title suggests that she sliced with a kitchen knife (a female housework symbol) through the uber-masculine political machine of Germany at the time (note the spinning gears and ball bearings in the composition). The Weimar Republic had just emerged following World War I as the first democratic German government. That would come to an end with the arrival of Hitler in 1933. What did she find inside of the cut out machine? The antiwar radical German Expressionist artist Käthe Kollwitz at the center! Her head is the one being thrown in the air by a body that is dressed in female dancer clothes. It is a moment of female victory. All across the collage, you will see powerful male figures: German politicians (e.g. the overthrown Kaiser Wilhelm II at the upper right), the current president, Friedrich Ebert (upper center), Communist leaders (Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin at the center right) and the recently-assassinated German Communist leader Karl Liebknecht (lower left). You will also find soldiers and symbols of military and industrial power. The revolutionary element in her collage is emphasized by images of crowds of German demonstrators. At the bottom right, there is a map of Europe highlighting countries that had recently given women the right to vote, juxtaposed with a photograph of the artist’s head. Placing photos of fellow Dada artists next to Marx and Lenin, with cutout words —“Die grosse Welt dada” (the great Dada world) is not arbitrary but a signal that their movement is revolutionary. The overall work is meant to declare that empowered women and Dada art are destabilizing the patriarchal culture. Höch’s ultimate mockery of the masculinity of her era was through sticking heads of military leaders onto the bodies of exotic dancers!

Hannah Hoch – Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919).

Hausmann composed a photomontage that was a harsh satire on the world of art of his day (view below). The subject of his work is a man with a cartoonishly large head, mouth and eyes. Despite the large eyes and mouth (and oversized pen), he sees and says nothing because they are actually hollowed out, i.e. he is a worthless art critic. He is perfectly coiffed and dressed in a double-breasted suit trying to blend in the upper society. A woman from that society is there to show him what she chooses to. His visiting card declares him to be: President of the Sun, the Moon, and the little Earth, Dadasopher, Dadaraoul, Ringmaster of the Dada Circus. At the back of his neck is a German 50-mark bank note that looks like you could rotate it like a key, as if he is a toy to manipulate with money.

Raoul Hausmann. The Art Critic. 1919-1920.

Raoul Hausmann, A Bourgeois Precision Brain Incites a World Movement, also known as Dada siegt (Dada Triumphs), 1920.

5. The Dada Cyborg: Look for disturbing man-machine fusions

Many years before sci-fi writers started contemplating a future where there might be a human-machine hybrid, Dada artists were among those who gave it thought and represented it in their artworks.

The Spirit of Our Time – Mechanical Head, Raoul Hausmann (1919)

The artist created a wooden dummy head that lacks any unique features or emotions. He attached a ruler, a piece of a typewriter, a small cup, a spectacles case and a watch, as if to say the modern man has become a perfect receptacle of information, without a soul!

A victim of Society (later titled ‘Remember Uncle August, the Unhappy Inventor’) Painting by George Grosz (1919).

The titles gives away the overall meaning of this photomontage. It is a suffering man (perhaps following the horrors of WWI). Is he physically disabled? Is he psychologically disturbed? There is a question mark on his head regarding his future or his fate. His face is disfigured by (or fused with) machine parts. Note that he has a spark plug for a nose. A razor is next to his neck. Perhaps, he’s contemplating suicide!

The Convict: Monteur John Heartfield after Franz Jung’s Attempt to Get Him Up on His Feet, 1920 by George Grosz

The subject who is a friend of the artist is depicted with a machine heart.

2. How Dada art got its name and what gave rise to it?

3. Why Dada artists were rebels?