1908 – 1918

Note: This page lists two phases of Futurism. The first and most important lasted from 1908 to 1918. The second was from 1929 to 1944.

1. Objects captured in motion, represented with repeated parallel lines and spirals to convey dynamism. In fact, repetition, blurring and lines of force, which are used to this day as techniques to convey a sense of movement, were conceived by the Futurists. The two paintings below are among the earliest in history to use such force lines to depict energy and motion.

Futurist art alternated between semi-abstract or completely abstract, i.e. some representations are deconstructed into geometric forms, influenced by Cubism, that the viewer could barely comprehend them.

Dynamism of a Car by Luigi Russolo (1913)

Abstract Speed – The Car has Passed by Giacomo Balla (1913)

The artist presents above a sublime fusion of blue sky, green landscape and pink exhaust fumes in an image of a car that had already passed.

2. One object in particular was of great fascination for the Futurists, that is a roaring car. They considered it the ultimate symbol of technological progress and modern innovation:

Velocity Of An Automobile by Giacomo Balla (1913)

3. Besides speeding cars, look for paintings glorifying steamships, trains, steel towers and urban construction.

Armored Train in Action by Gino Severini (1915)

This is one of the most iconic Futurist paintings. It combines most elements that distinguished the art movement. We could even count them: Glorification of war – check. Celebrating speed and momentum – of course. Celebration of modern technology and industrialization – check. An aerial view – absolutely! Machinery’s dominance over nature – check. In brief, it’s an Italian military train piercing through the countryside. It’s filled with soldiers aiming their rifles in the same direction. Smoke from their guns and the cannon eclipses the green landscape. The soldiers are faceless, as if the artist wants to say these men do not matter as individuals, their military mission is all that matters. The light blue or dark grey is the color of metal, the body of the train (a strong symbol of industrialization). Note the Cubist influence in the use of multiple perspectives simultaneously. Severini created this artwork in 1915 when WWI in Europe was in full swing. Seeing this gorgeous, colorful masterpiece, you could almost forget about the true reality of WWI: the rat-infested trenches and the rotting, abandoned dead soldiers.

States of Mind I: The Farewells by Umberto Boccioni (1911)

In this painting, we could see a train crowded with passengers. The figures are green and are almost fused with the train and its smoke. Everything is in motion, the train, its steam and the passengers. A few items are stationary though like the number of the train station and the oil tower in the background.

The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli by Carlo Carrà (1911)

Angelo Galli is an Italian anarchist who was killed in 1904 by police during a general strike. To prevent the funeral from turning into an anti-government parade, officials refused the entry of mourning anarchists into the cemetery. The mourners resisted, then a violent scuffle erupted between them and the police. The artist wanted to share, what he considered, a heroic moment with his viewers. The scene shows a chaotic and brutal fusion of police mounted on horseback and angry mourners. Both sides are armed, clubs and lances are in their hands. Galli’s anarchist supporters are dressed in their typical black and waving black flags. Light emanates from both the sun and the red coffin in a symbolic gesture. The clashes are so violent that the coffin seems as if it could fall off the shoulders of pallbearers at any moment.

4. Look for paintings celebrating industrial landscapes and modernity

Skyscrapers and Tunnel by Fortunato Depero (1930)

The City Rises by Umberto Boccioni (1910)

The artist shows a modern city rising. There’s a major building in construction in the background. In the foreground, we see the workers, some of whom are trying to overpower a horse. The whole scene is in motion. All the painting’s subjects are blurred and fused together to create a sense of dynamism.

Brooklyn Bridge by Joseph Stella (1919)

When the Italian artist Joseph Stella arrived in New York, he was fascinated by the Brooklyn Bridge. Like fellow Futurists, he had an optimistic attitude towards modern life. He used the bridge as an industrial symbol for American progress and technical superiority. The painting is almost spiritual with no humans to find. The entire structure seems fractured and light is emanating from glass-like parts to resemble stained glass of an old cathedral. It’s as if these structures are the new shrines which people should visit and regard with awe.

5. Unlike Impressionist artists, the Futurists did not admire natural light. The Futurists sang the praises–literally, as in the founder’s prose–of artificial light. Electrified city lighting, the street lamp, was a new and unmistakable symbol of technological progress.

Street Light by Giacomo Balla (1910)

Aeropittura (Aeropainting): The Second Wave of Futurism

1. Before Futurism completely disappeared, it made a comeback that was no longer about automobilism but aeromobilism, i.e. they replaced their fetish of a roaring car with a soaring airplane. That second phase lasted from 1929 to 1944, the year Marinetti, the Futurist ringleader, died. The paintings depict cinematic views of airplanes and aerial combat, both representing a technology that was a great source of national pride in Italy. Note, biplanes feature heavily in aeropittura (aerial painting) as well as the cityscape of Rome. The Futurists, and their fascist allies, yearned for the greatness of ancient Rome while dreaming of a modern, industrialized Italy .

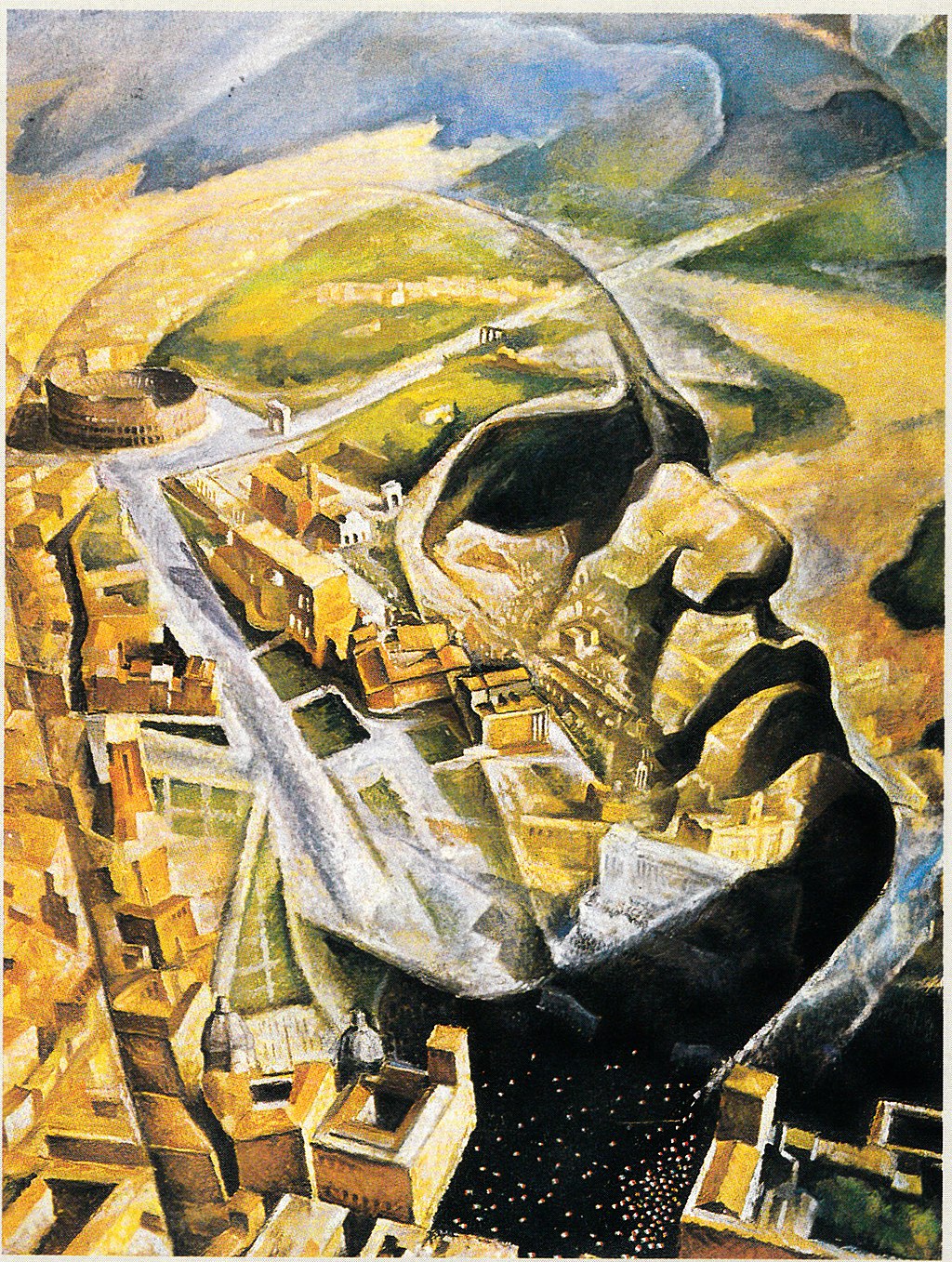

Flying Over the Coliseum in a Spiral by Tato (Guglielmo Sansoni) (1930)

This painting shows a bird’s eye view of a world in motion. The airplane flying over the Coliseum is meant to associate modern Italy with its ancient past. In other paintings, artists went further by playing along with the Fascist government and associating its leadership with the Roman empire. (View below Mussolini the Aviator by Alfredo Gauro Ambrosi).

2. Look for paintings of dizzying, nose-dive views of the city. The aviator in these artworks is shown as a great hero.

Before the Parachute Opens by Tullio Crali (1939))

A heroic portrayal of a lone parachute soldier plummeting fast towards to the ground.

Nose Dive on the City by Tullio Crali (1939)

Upside Down Loop (Death Loop) by Tullio Crali (1938)

The painter decided not to depict the pilot in this breath-catching painting. He chose to put you in the pilot’s place during an aerobatic maneuver. What we see is an upside down view of Rome from the cockpit.

3. A powerful theme of Aeropittura, and a favorite subject of Futurists towards the end of their art movement, was the portrayal of the Italian Fascist leader, Benito Mussolini, in quasi-religious fashion. They combined his intimidating face with aerial landscapes of Italy to portray him in an eternal and invincible image.

Mussolini the Aviator by Alfredo Gauro Ambrosi (1930)

A propagandistic painting depicting Mussolini’s profile projected on the great city of Rome.

Portrait of Il Duce by Gerardo Dottori (1933)

The portrait of the Fascist leader is rising out of the Italian landscape. Biplanes surround his portrait in a semi-religious symbol of protection and absolute power.

2. How Futurism got its name and what gave rise to it?

3. Why Futurist artists were rebels?